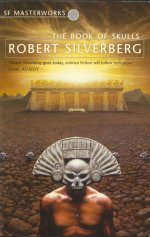

| Robert

Silverberg Robert Silverberg was born in New York City in 1935. In 1949 he started a science fiction fanzine called Spaceship and made his first professional sale to Science Fiction Adventures, a non-fiction piece called "Fanmag," in the December 1953 issue. His first professional fiction publication was "Gorgon Planet," in the February 1954 issue of the British magazine Nebula Science Fiction. His first novel, Revolt on Alpha C, was published in 1955. In 1956 he graduated from Columbia University, with a major in Comparative Literature, and married Barbara Brown. After many sales, he earned a Hugo Award for his promise (the youngest person ever to do so). In the summer of 1955, he had moved into an apartment in New York where Randall Garrett, an established science fiction writer, lived next door; Harlan Ellison, another promising young novice, also lived in the building. Garrett introduced Silverberg to many of the prominent editors of the day, and the two collaborated on many projects, often using the name Robert Randall. He divorced his first wife in 1986 and married writer Karen Haber the following year. He now lives in the San Francisco area. |

| Knjiga

lobanja Robert Silverberg Yet despite this knowledge, people go through their lives

working, creating, asserting themselves, and somehow or another

seeking to leave their imprint on this world. Religion, science,

medicine, technology -- these all offer some vague promise of

immortality, and maybe it is this promise that keeps the bulk of

mankind moving forward and in some sense hopeful.

But what happens when the promise of immortality lies directly

and clearly ahead, a path to be followed absolutely or ignored

forever? How would we respond if we knew we could live forever, but

that it would require absolute dedication, unfailing pursuit,

regardless of the personal costs? This question is addressed by

Robert Silverberg in his classic novel, The Book Of Skulls,

reprinted in the SF Masterworks series by Millennium.

Having discovered an archaic text promising eternal life to those

who are willing to pursue it, four college boys -- Eli, Ned, Oliver,

Timothy -- begin this pursuit of immortality in a kind of

Kerouac-like road trip across the country, driving fast, smoking

cigarettes, having sex, and generally discovering themselves. To a

point.

But the trip is not driven by a sense of searching or unrest.

Instead, its goal is clear. An encampment deep in the Arizona

desert, where the promise of eternal life glimmers like a mirage,

tantalizing but of uncertain solidity. And when they finally arrive,

they begin to discover things about themselves that make them wonder

whether eternal life is really worth the cost.

What initially seems like a harmless lark quickly takes on more

somber tones as it becomes clear that the promised eternal life is

not for all. Everything has its price, and even as they leave their

Ivy League haven on little more than a spring break road trip, these

boys know that if they do discover eternal life, it will only be for

two of them. For the book clearly states that two must die so that

two may live. But to think about that too often would be crippling,

in the same way that thinking about death too often would cripple

our enjoyment of this life.

These boys are not friends, and that is the remarkable thing

about Silverberg's writing. There is no sense that these four really

belong together, no esprit de corps that keeps them unified

and constant. Instead, it is simply their curiosity, their desire to

see something finished once it has been begun that drives them. In

other words, it is their common humanity that keeps them together,

despite their significant differences. And for all their

differences, Silverberg makes each of these boys richly human.

At the heart of it, The Book Of Skulls is a study of

psychology, perhaps even sociology. The boys are individuals, young

men, but they are also types to some extent, and they are forced to

live (and risk death) together to achieve a common goal. The Book

Of Skulls is a masterful presentation of the differences that

keep mankind always in flux, but also of the likenesses that allow

us to achieve our goals. Even when we want to live forever. |

To

live forever -- that has been a dream of mankind since we first

began to dream. Perhaps one of the curses of self-awareness is

knowing that inasmuch you exist now, there will be some time in the

not-too-distant future when you no longer exist. At least not in the

sense that you currently understand existence. No matter how hard

you try to ignore it, this knowledge remains behind all of your life

and all of your actions.

To

live forever -- that has been a dream of mankind since we first

began to dream. Perhaps one of the curses of self-awareness is

knowing that inasmuch you exist now, there will be some time in the

not-too-distant future when you no longer exist. At least not in the

sense that you currently understand existence. No matter how hard

you try to ignore it, this knowledge remains behind all of your life

and all of your actions.